This article looks at the COVID-19 pandemic response in Argentina, with a particular focus on the judicial control of public health policies. Looking ahead, we discuss the mechanisms that need to be implemented in order to avoid undue judicial interference, which is particularly critical in countries like Argentina, where the Judiciary is delegitimized and strongly questioned.

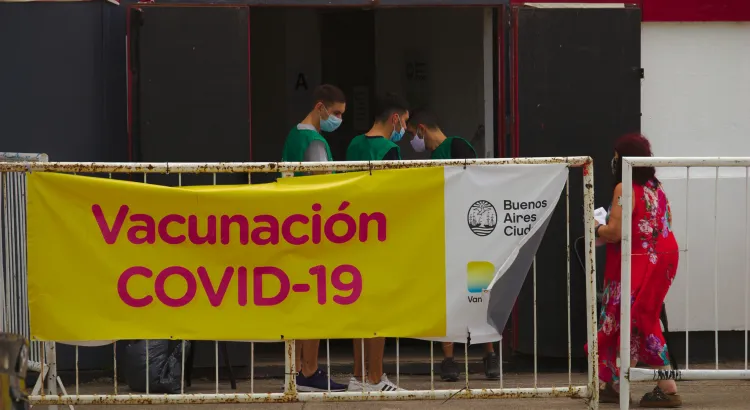

We focus on a case in Argentina where a federal judge ordered the suspension of the campaign for pediatric vaccination against COVID-19.

The case has parallels to rulings in the U.S. and elsewhere. For example, in their discussion of a case in which a federal judge in Florida, appointed by then-President Trump, issued an injunction to block nationwide the transit mask mandate, Sarah Wetter and Lawrence O. Gostin point out that it is necessary to limit the use of court orders at the national level.

This same pattern of prosecution of public health policies and resolutions adverse to collective health was repeated in Uruguay, Brazil, and other countries in the region. There, too, single judges decided on important social and health issues. And they did it with a wide scope, without all the necessary elements of judgment, in record time, without specific training in public health, and with interference in other branches of the State. They thus undermined public policies established by the Executive Branches in the framework of a Global vaccination strategy.

The Argentine case: suspension of pediatric vaccination COVID-19

On November 30, 2022, Federal Court No. 4 of Mar del Plata decided the case “Carrillo Couhez, María Alicia Noemí and Others v/ National Executive Power and others/ Collective Amparo” (File No. SB/LC/JGI/VC 14056/2022). The plaintiffs requested that the inoculation of the COVID-19 vaccines in children between 6 months and 16 years of age be suspended without further ado, considering these medical acts to be in violation of the law and the Constitution, as well as being potentially risky for children. The Federal Court declared itself competent to understand the proceedings and granted the request.

The measure was appealed and on December 29, 2022, with sound criteria, the Mar del Plata Federal Court of Appeals annulled it.

The main arguments of the Chamber to support its decision can be summarized in five points:

1) The judiciary is not legitimized to design public policies.

2) By acting in the manner in which he did, the judge in the first instance violated the division of powers and the constitutional and republican principle of government.

3) The judiciary should not interfere in the vaccination campaign, since the framework of judicial action is restrictive when it comes to controlling the constitutionality of public policies.

4) The acts of the public administration are presumed legitimate and, therefore, the precautionary measures must abide by an eminently restrictive criterion.

5) Vaccination is not mandatory, “which prevents any person who has doubts about the efficacy of vaccines, or about their innocuous nature, from suffering harm.”

In this line, the court also pointed out that in any vaccination campaign there is a clear, committed public interest that demands even greater caution from judges when evaluating the acts of the Public Administration.

We believe that, thanks to this resolution, it was possible to guarantee the due protection of the right to health, since it placed the collective interest, public health, and the common good at the center of the matter.

On the other hand, it is important to point out that, although the resolution of the Chamber has technical, legal, and health implications, above all it allows us to recover responsibility, reasonableness, and trust in State institutions. In other words, it realizes the ethical dimension of judicial action. This is unlike the first instance decision, which put the National Vaccination Plan at risk, and which did not analyze or refute the basic aspects of local, national, and global health policy. Instead, the judge ignored the strict Regulatory Authorities’ vaccine approval mechanisms and procedures, underestimated the severity of COVID-19, overestimated the individual rights of those who promoted the action (instead of ensuring the collective interest), and underestimated the importance of vaccination coverage rates

The seriousness of the matter is clear, since this decision had the potential to put the population at risk, delay the end of the pandemic, affect vaccine coverage rates, delegitimize state institutions, undermine citizen trust in the health authorities, and exacerbate the situation of vulnerable groups.

Concern about judicial interference in public health policies

Various civil society organizations and global and regional coalitions such as Vaccines for People in Latin America (PVA LAC) observed with concern the issuance of the first ruling, since it had an impact on global efforts for the prevention and control of COVID-19. Worse still, it did so in clear ignorance of the international commitments assumed by the country within the framework of the International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005) and the recommendations of the World Health Organization regarding immunization and the preparation, prevention, and control of pandemics.

In general terms, beyond the specific case, we consider that one-person decisions such as that of the first judge in this case make visible problems inherent to the jurisdictional system and trigger relevant questions. Especially if we start from what Daniel Swartzman maintains about the use of strategic litigation that affects public health: “it seems that we have not learned the lesson that all our legislative advances will be routinely questioned in court.”

Among other questions, it is worth asking: (i) Is the current procedural regulation in the field of class actions, like the one brought by the plaintiffs against the vaccination campaign, adequate?; (ii) how should we define the role, scope, and limitations of the Judiciary in the prosecution of conflicts of public interest?; and (iii) beyond collective processes, is it necessary to have a special process for judicial control of public policies?

Regarding this last issue, Verbic and Berizonce affirm that it is necessary to have a legal regulation that establishes a special process for conflicts that involve the treatment of public policies by the Judiciary, since such cases put in tension the interpretation of the republican principle of division of powers and the rules of democratic procedure.

There are still many pending challenges for the judiciary. To face them, it is crucial to training the judiciary in public health and human rights to allow the full realization of the population’s right to health to be achieved, while at the same time incorporating new tools and dialogic methods for resolving structural conflicts.

+++

For further reading, see:

- Ruling: The CSJN ordered the parents of a child to get vaccinated. “NN or D., v. s/ protection and guard of people”

- The new regime of precautionary measures against the National State established by Law No. 26,854 and its potential impact in the field of collective proceedings

- Abeledo Perrot Commercial Law Magazine Nº 233 Adequate representation in North American Class Actions

- La Ley Magazine (Argentina) Judicial Control of Public Policies (About a Brazilian Bill)

- Verification of the essential precautions where it systematizes presents and agreements issued by the CSJN.

- On the International Sanitary Regulations.

María Natalia Echegoyemberry is an affiliated researcher with the Petrie-Flom Center’s Global Health and Rights Project. She teaches at the University of Rosario in Argentina and works with communities and vulnerable groups in the country to generate public policy proposals at local, national, and regional levels that promote economic, social, cultural, and environmental rights.

Francisco Verbic is an attorney specializing in complex and public interest litigation, class actions, access to justice and judicial reform.